LANCET COUNTDOWN ON HEALTH AND CLIMATE CHANGE

POLICY BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

The 2024 Lancet Countdown Brief for the United States (U.S.) highlights national data on the health impacts of climate change and progress on climate action from the 2024 report of the Lancet Countdown.c1 It highlights three priority opportunities for an incoming administration of any party to center health in its approach to climate action. The Brief is supported by a diverse group of health experts from over 80 organizations in the U.S. who conclude that human health must be a core measure of successful climate action. As such, there is an urgent need to transition from fossil fuels towards non-combustion renewable energy and a climate-resilient society that is healthy, just, and equitable.

Introduction

Climate change has created a health crisis that will continue to worsen unless the U.S. takes decisive action to end its fossil fuel dependence, reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and invest in strong health systems and climate resilience. An equitable fossil fuel phase-out requires proactive attention to the health and well-being of both the historically marginalized communities impacted by fossil fuel pollution and the communities and fossil fuel workers most impacted by the clean energy transition. Such a transition will improve the health of everyone in the U.S. and strengthen our nation in other fundamental ways, benefiting our economy, security, and the wellbeing of current and future generations.

U.S. climate policies have substantial impacts on human and planetary health. Climate action can deliver cleaner and healthier air, healthier diets, stronger and climate-resilient health systems, more resilient communities, equitable access to affordable and clean energy, and reduced social inequalities.

Since 2018, the Lancet Countdown U.S. Briefs have tracked the tolls climate change and fossil fuel pollution are taking by increasing illness and premature death, deepening existing health inequities, and limiting growth and prosperity – especially in under-resourced communities subjected to marginalization. The Briefs have also highlighted opportunities to improve health and wellbeing through rapid reductions of GHG emissions and other fossil fuel pollution, increased federal investments in non-combustion renewable energy sources, health sector action to reduce emissions and increase resilience, and U.S. leadership in global commitments to support mitigation, adaptation, and climate justice.c2, c3, c4, c5, c6, c7

Under the current administration, the U.S. has taken significant steps to meet ambitious climate goals. In 2021, after rejoining the Paris Agreement, the U.S. set a goal to cut its GHG emissions in half (from 2005 levels) by 2030 and achieve net zero emissions by 2050.c8 The 2021 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) laid the groundwork for the largest climate investment in U.S. history, allocating nearly $370 billion in incentives to climate, clean energy, and community-oriented environmental justice initiatives. This was accompanied by other major investments in climate action through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) advanced regulations on fossil fuel pollution, finalizing rules setting stronger air pollution standards and reducing GHG emissions of methane and carbon.c9, c10 Indeed, in 2023, U.S. GHG emissions declined while our national economy grew.c11

Despite this progress, children born today can expect poorer air quality, hotter days, and lifelong social and community disruptions from climate change.c12, c13 Climate change is harming all aspects of health and wellbeing for people in the U.S.c14 – and climate-related losses continue to mount. 2024 is another record-breaking year of climate-related extreme weather events, adding to the rising burden of health harms from climate change. Record-breaking heat was experienced across the U.S.;c15 in September, nearly a third of the U.S. was in a state of drought; Hurricane Helene resulted in hundreds of deaths and as yet unknown impacts on health, economic, and social well-being;c16 and Hurricane Milton followed closely, causing cascading impacts.c17, c18 Globally, climate-related extreme weather events continue to rise, causing major health and economic damages.c19

Recommendations

This year’s Brief reviews progress toward policy recommendations from previous U.S. Briefs. It highlights key opportunities to build on recent progress and to align U.S. policy and commitments more closely with the fundamental goal of prioritizing health and health equity as key measures of successful climate action. A summary of U.S. specific indicators from the 2024 report of the Lancet Countdown can be found in the accompanying 2024 U.S. Data Sheet.ci

Rapidly reduce fossil fuel production and use while accelerating the transition to clean, non-combustion renewable energy to improve health and health equity.

Rapidly reduce fossil fuel production and use while accelerating the transition to clean, non-combustion renewable energy to improve health and health equity.

-

1.1

End new commitments to fossil fuel extraction and infrastructure and rapidly phase out existing production and use

-

1.2Accelerate electrification by rapidly scaling up the production, storage, and transmission of non-polluting, non-combustion renewable energy

-

1.3Reduce methane emissions

-

1.4Invest in equitable active transport and zero-emission public transportation

-

1.5Phase out fossil fuel investments and subsidies, reinvesting in healthy climate action

Build resilient, adaptable communities and support public health to protect people from climate impacts.

Build resilient, adaptable communities and support public health to protect people from climate impacts.

-

2.1Recognize health system vulnerabilities and invest in readiness and resilience

-

2.2Invest in strong public health systems and support public health readiness for climate change

-

2.3Leverage infrastructure and built environment investments to maximize community health and resilience

Build U.S. global leadership through scaling up global investments and support for climate and health action.

Build U.S. global leadership through scaling up global investments and support for climate and health action.

-

3.1Expand U.S. contributions to global climate finance in line with need and scale of investments in other global challenges

-

3.2Retool global climate, health, and development investments to achieve interconnected climate and health goals

-

3.3Support changes to the global financial architecture, including debt structures, to enable greater investment in health and social systems

Recommendation Details

Rapidly reduce fossil fuel production and use while accelerating the transition to clean, non-combustion renewable energy to improve health and health equity

Rapidly reduce fossil fuel production and use while accelerating the transition to clean, non-combustion renewable energy to improve health and health equity

Six prior U.S. Briefs called for national, state, and local policies to support the immediate phase-out of fossil fuels and hasten a just and rapid transition to non-combustion renewable energy to meet public health and climate goals. Centering health in climate policy requires that the U.S. put as much effort into ending its fossil fuel consumption and production as it does into promoting the use of renewable energy.

U.S. actions on a national level remain inadequate to reduce emissions to a level compatible with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recommendations to keep global temperatures well below 2°C, let alone 1.5°C, which is considered critical to protect health – now and in the future.c20 In 2022, the U.S. production of goods and services was responsible for 13.5% of all global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions; this number rises to 15.9% of global emissions when considering consumption of goods and services (including those imported). By either accounting, the U.S. is the world’s second greatest emitter of CO2 (Indicator 4.2.5).

Future U.S. climate policy must contend with two important trends: increasing demand for electricity and persistent investments in fossil fuel infrastructure. Major new investments to scale up renewable energy have resulted in modest progress, yet fossil fuels continue to constitute the majority of electricity generation. In 2022, renewable energy accounted for only 3.1% of the total energy supply in the U.S. (Indicator 3.1.1).cii This same year, 21.4% of electricity came from renewables, up from 9% in 2017.c21 Fossil fuels continue to constitute a significant share of electricity generation. In 2022, coal made up 11% of the U.S. total energy supply (Indicator 3.1.1). As coal generation has declined, gas generation has increased. Although annual CO2 emissions from the U.S. energy system have been slowly decreasing since 2000, they increased 7% from 2020 to 2021 – the largest year on year increase in two decades (Indicator 3.1.1), primarily due to the economic recovery following the COVID-19 pandemic.c22 Non-combustion renewable energy sources must be scaled up to meet growing demand such that fossil-based energy generation is not required to fill supply gaps.c23

Recommendation 1.1. End new commitments to fossil fuel extraction and infrastructure and rapidly phase out existing production and use

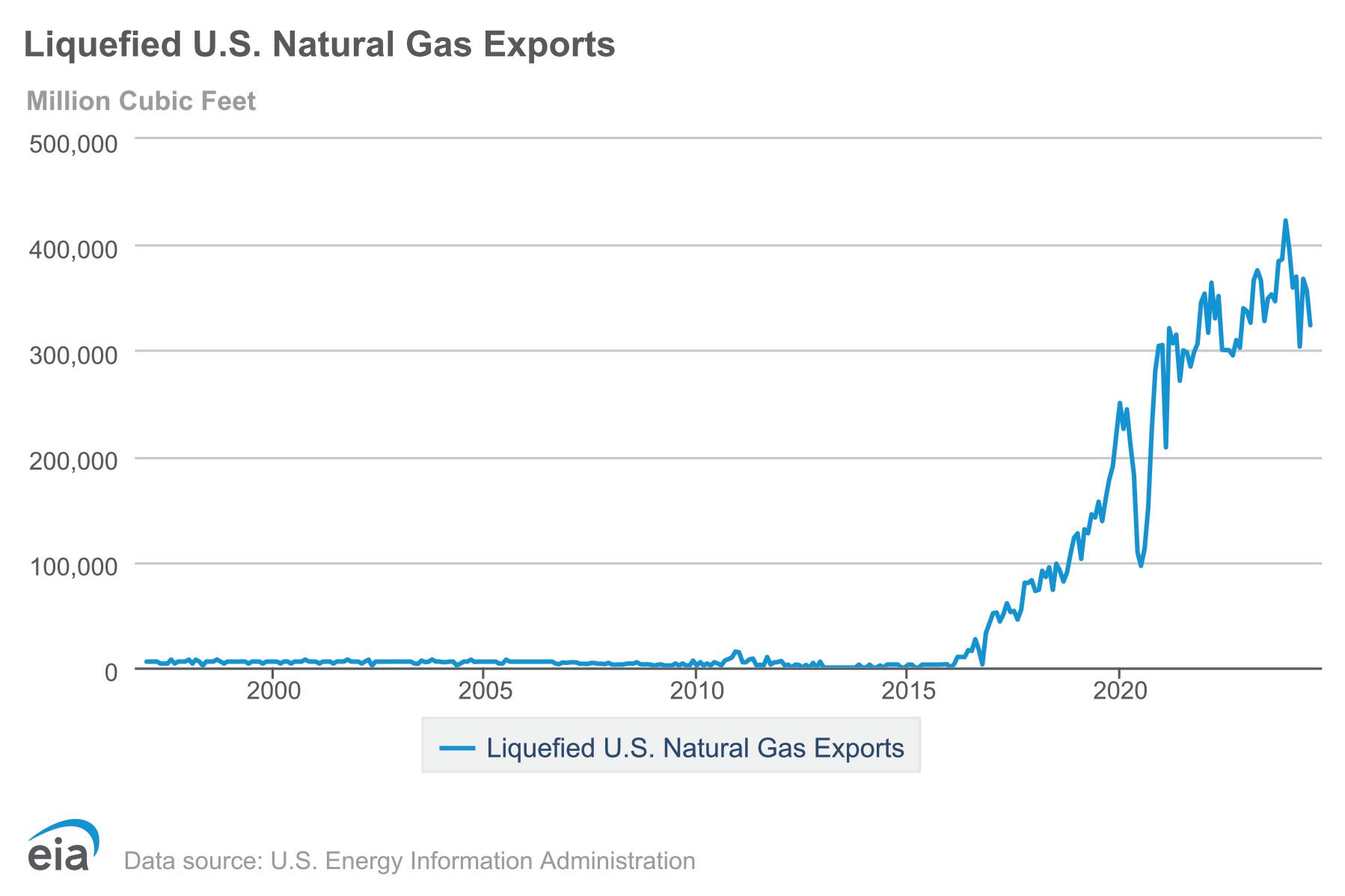

In 2021, fossil-fuel related air pollution was responsible for about 50,000 deaths in the U.S. (Indicator 3.2.1). Despite the adverse health consequences of its fossil fuel use, the U.S. continues investing in fossil fuel infrastructure and is a major exporter (example in Figure 1).c24 With the recent rapid growth in fossil fuel exports and the use of fossil fuels as the raw materials for plastics and other petrochemicals, it can no longer be assumed that growth in renewables will offset fossil fuel production. Regardless of its transition to renewables domestically,the U.S. will slow the energy transition globally if it continues to export fossil fuels.

More focus must be placed on ending fossil fuel production.c25 To meet global climate goals, the U.S. must increase renewable energy production while rapidly reducing fossil fuel extraction, production, and use; ceasing the construction of all new fossil fuel infrastructure; and ending licensing of new fossil fuel exploration and extraction on federal and state lands.

Figure 1. U.S. exports of natural gas, 1998 – 2024

Centering Communities in Just Transition Pathways

Recommendation 1.2. Accelerate electrification by rapidly scaling up the production, storage, and transmission of non-polluting, non-combustion renewable energy

The U.S. has made progress in electrifying certain sectors, including transportation, building heating and cooling, and some industrial processes. This has benefited health in the process. For example, adoption of wind and solar led to an estimated 1,200 to 1,600 fewer premature deaths in the U.S. in 2022, and contributed to $249 billion U.S. dollars (USD) in climate and air quality benefits from 2019 through 2022.c27

Electricity demand is expected to rise in the U.S. and globally. To ensure that renewables can meet growing demand, there must be a comparable acceleration in the production, distribution, and storage of non-combustion renewable energy.c23 Supporting an equitable transition to renewables requires meaningfully engaging local communities in energy policy decision-making and governance to address scalability, feasibility, acceptability, equity, and environmental justice concerns.c28, c29, c30 It also requires ensuring equitable access to renewable energy technologies, affordable clean and healthy energy, energy efficiency solutions, and the economic benefits and jobs of the expanding renewables sector.c31 Considering health and equity across the life cycle of renewable energy technologies is important to protect the health of workers in the renewable energy and mining sectors and the communities living near extraction and production sites. This includes through the responsible sourcing of batteries, critical minerals, and other inputs to the renewable energy transition.c32, c33

Ensuring that the future energy system promotes health requires investment in solutions that result in verifiable GHG emissions reductions, do not harm health or health equity, and do not involve fossil fuels in the supply chain. For example, ~95% of hydrogen in the U.S. is sourced from methane gas,c34 and hydrogen technologies contribute to air quality-related health impacts.c35 Similarly, much of the CO2 used in carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) is used to produce more oil through enhanced oil recovery, with consequences for air pollution.c36, c37, c38 Solutions should be prioritized to promote health and health equity, reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, and reduce air pollution.c6

Better accounting of climate-related health harms can support strategic investment

Expanding economic estimates to include the full range of health damages is critical. The U.S. can demonstrate global leadership by including health damages in climate change cost estimates. Investments in climate mitigation and adaptation are often bolstered by benefit-cost analyses; thus, adequately reflecting the full health costs of climate change in these analyses can more clearly demonstrate the value of investments in climate action. For example, EPA’s final rule to reduce methane from the oil and gas sector used estimates of the costs of climate change (sometimes referred to as the social cost of carbon) that incorporated temperature-related mortality into a separate health damages category. Temperature-related mortality is a small portion of the estimated health costs associated with climate change, yet these health damages alone still accounted for $104 – 179 of the $219 – 233 cost estimate (in 2020 USD per metric ton of CO2).c39, c40, c41 Economic guidance may contribute to and signal similar policy decision-making tools globally.

Recommendation 1.3. Reduce methane emissions

Methane is a fast-acting GHG that has substantially more warming potential than CO2, making it a key target for achieving climate goals and decreasing climate change and health risks in the near-term. Methane emissions are estimated to be 12% of total U.S. GHG emissions,c42 largely coming from oil and gas production, the methane gas supply chain, landfills and food waste, sanitation infrastructure, and agriculture.c43, c44

The recently finalized Methane Rule imposes new regulations and monitoring requirements on the oil and gas sector.c45 The BIL and IRA also address methane emissions through the Methane Emissions Reduction Programc46 and Climate Pollution Reduction Grants.c47 They also include initiatives to place a waste emissions fee on methane emissions from oil and gas production and provide funds to stop methane leaks and plug orphaned and abandoned oil and gas wells.c48 Health benefits from these actions include reductions in toxic air and water pollutants, including volatile organic compounds, nitrous oxide, and ozone formation.c49, c50, c51 Full implementation of these programs must be accompanied by additional efforts to address methane emissions through policies that monitor, detect, and reduce methane emissions across all sectors – including agriculture.

Recommendation 1.4. Invest in equitable active transport and zero-emission public transportation

In 2021, fossil fuels accounted for more than 93% of all road transport energy, and electricity accounted for less than 1% (Indicator 3.1.3). Traffic-related air pollution contributes to climate change and is a major cause of health harms. Racial and ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure persist and in some cases are rising, even as overall air pollution levels decrease.c52, c53 Specific attention to reducing air pollution in the most impacted communities must be a focus of transportation investments.c54

Investments in active transport (e.g., walking, biking) and zero-emission public transportation (e.g., electric buses and trains) have a wide range of physical and mental health benefits, while also supporting expanded employment opportunities and building social capital.c55, c56 These physical activity-related and mental health benefits far outweigh the costs of large-scale active transport infrastructure.c57 Focusing on equity and engaging at risk communities is important in efforts to improve access to safe walking or biking – especially among low-wealth communities and communities of color – which currently have the lowest rates of active travel in the U.S.c58

The BIL and IRA increased investments in transportation electrification, such as through the Safe Streets for All program and the Active Transportation Infrastructure Investment Program.c59, c60 The increasing market share of electric vehicles, supported by charging infrastructure growth, is benefiting health by reducing air pollution.c61, c62 Electric vehicles can improve health equity by reducing air pollution in disproportionately impacted neighborhoods, particularly if the focus on electrification of medium and heavy-duty vehicles and school buses continues.c63 Other equity-based strategies include using transfer hubs outside of city limits for long-haul trucking routes, which allow urban travel to be electrified – reducing urban air pollution – until truck electrification battery size constraints are resolved.c64

Future actions should focus on improvements in health outcomes, particularly in disproportionately impacted communities, through continued vehicle electrification, optimizing placement of charging infrastructure to maximize equity, and emphasizing active and public transportation to maximize reductions in transport-related GHG emissions.

Recommendation 1.5. Phase out fossil fuel investments and subsidies, reinvesting in healthy climate action

There are opportunities to reform the existing financing system to support investments that align climate and community health. In 2022, the U.S. had a net-negative carbon revenue, indicating that fossil fuel subsidies were higher than carbon prices. The U.S. allocated $9 billion USD in fossil fuel subsidies in 2022 alone (Indicator 4.3.3), while other estimates suggest domestic subsidies are much higher.c7 Shifting public investments away from fossil fuel extraction can expand resources for investment in the transition to non-combustion renewables and other health protective climate action.

Increase investment in health system mitigation, readiness, and resilience

The healthcare sector accounts for 8.5% of U.S. GHG emissions,c65 yet this sector lags behind others in sustainability management, accountability, and transparency.c66 No national program requires the U.S. healthcare sector to measure, manage, and disclose verified environmental sustainability data, as is seen in countries such as the United Kingdom, which has set a goal of net zero by 2045.c67

Several voluntary programs exist. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Health Sector Climate Pledge invites health organizations to commit to reduce GHG emissions and create climate resilience plans.c68 The Joint Commission’s Sustainable Healthcare Certification program encourages emissions reduction by providing a framework and opportunities for public recognition.c69, c70 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will launch their TEAM Decarbonization and Resilience Initiative in 2026 to support hospital GHG emissions reporting, tracking, and reduction.c71 However, action by health systems remains the exception rather than the rule, as most health systems have yet to establish emissions reduction goals or create climate resilience plans.

No programs require public disclosure of verified emissions data, making it difficult to determine the impact of current efforts and hold organizations accountable.c72 Some states are moving to increase transparency. In California, SB 253 requires organizations with annual revenues over $1 billion to report Scope 1 and 2 emissions,c73 while Massachusetts will require all acute care hospitals to report Scope 1 and 2 emissions starting in 2025.c74 The health care supply chain is large, globally connected, and a major source of the sector’s emissions. International and federal sustainability accounting regulations for corporations, such as European reporting standardsc75 and new investor reporting rules in the U.S.,c76 may also affect the health sector’s emissions reporting.

To accelerate meaningful progress, the HHS Office of Climate Change and Health Equity, EPA, Department of Energy (DOE), and other federal agencies should expand technical assistance and funding to aid emissions reduction and resilience efforts, including guidance on how to use the IRA’s tax credits, grants, and other incentives to support climate action.

Additional opportunities to reduce health sector emissions include developing a national reporting platform and standardized metrics for sustainability data to transparently track the sector’s progress, including implementation of Science Based Target Initiatives related to accreditation status; federal mandates for healthcare sector decarbonization; policy action to eliminate barriers to telehealth; and improved coordination of high-value care.

Build resilient, adaptable communities and support public health to protect people from climate impacts.

Build resilient, adaptable communities and support public health to protect people from climate impacts.

The health and socioeconomic impacts of climate change continue to accelerate and will persist into the future, even with full implementation of climate mitigation policies. Rural, marginalized, low wealth, and fenceline communities often bear the greatest burdens of climate change impacts, and children and older adults are particularly vulnerable.c6, c14 Over 80% of U.S. cities reporting on their climate action have undertaken a climate risk and vulnerability assessment (Indicator 2.1.3). Translating these assessments into adaptation and resilience action to protect the health of impacted communities is a critical next step.

Building resilient communities and health systems will take time. Since its inception, the U.S. Brief has consistently called to support a healthy built environment, strengthen social infrastructure and community connections, address health-related vulnerabilities, and support community adaptation. This includes focusing on occupational risks, expanding research and education initiatives, and developing a green-collar workforce skilled in jobs that promote sustainable practices. Prioritizing investment in historically under-invested or disinvested communities via the Justice 40 initiative and other targeted initiatives is vital to enhancing the resilience and adaptability of communities harmed by the legacy of systematically inequitable policies and ensuring their future well-being.c77 Dramatically scaling up support for community and public health action, including action to respond meaningfully to the mental health impacts of climate change, is also necessary.

Recommendation 2.1. Recognize health system vulnerabilities and invest in readiness and resilience

Rising climate impacts on health place large burdens on health systems by increasing demand for health services. Tropical cyclones in the U.S. cause thousands of excess deaths, with excess mortality persisting for many years after an extreme weather event.c78 The incidence of many climate-sensitive diseases, including vector-borne and zoonotic diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, Lyme disease, and West Nile virus, may increase as vectors expand into new areas (Indicator 1.3).c79, c80 Climate disasters can increase demand for mental health services.c81

While health systems wrestle with increased demand, a large proportion of U.S. healthcare infrastructure is vulnerable to damage and supply chain interruptions from extreme weather. The emergency care system, including emergency medical services and emergency departments, regularly operates at capacity – particularly in rural areas – compromising surge capacity. Extreme heat events, wildfire smoke, floods, storms, and worsening air pollution exert pressure on health system capacity.c82, c83 For example, Hurricanes Helene and Milton in September and October 2024, respectively, ravaged the southeast U.S., compromising medical care across the region, endangering patient lives, closing hospitals, and causing staff and patient evacuations, as well as contributing to supply chain shortages of critical medical supplies such as intravenous and dialysis fluids. c84, c85, c86

The U.S. needs greater federal investment in systematic risk assessments of healthcare systems and pathways for resilience. Health system financing has yet to fully integrate climate risks, potentially complicating recovery from disasters for the large proportion of U.S. healthcare facilities that are not capitalized to fully fund disaster recovery.c87 Rural hospitals provide the majority of healthcare in rural communities,c88 but funding and closures are a persistent concern for these facilities.c89 Solutions are needed to address both health systems vulnerabilities and inequities across both rural and urban healthcare systems and communities.

To increase resilience, future investments could stress test health facilities and operations against climate-driven disasters, integrate health systems capacity into hazard mitigation planning, and promote community resilience planning and inclusion of environmental information into health information systems to support screening and care coordination for patients. Funding for facility hardening and disaster risk reduction is crucial to maintaining the continuity of operations for healthcare institutions.

Recommendation 2.2. Invest in strong public health systems and support public health readiness for climate change

Public health systems are integral to protecting and improving community health and coordinating health-protective action on the social determinants of health across sectors. Public health programs across the U.S. are under strain from climate change and other stressors and are under-resourced to address these impacts.c90, c91 The IRA significantly increased funding for energy efficiency and environmental sustainability in state, local, Tribal, and territorial health departments. However, a number of additional investments are needed to ensure that public health systems can carry out their own missions and support other sectors as the climate changes.

Congress must adequately fund national climate and public health programs including the HHS Office of Climate and Health Equity and the CDC’s climate and health program, which partners with health departments to increase resilience using the Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) framework.c92, c93 It is critical for federal and state leaders to additionally expand investments to strengthen local, state, Tribal, and territorial health departments to prepare for and respond to climate-related health threats.

According to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), the U.S. health sector receives data from the meteorological sector, including data services, climate monitoring, climate analysis and diagnostics, climate prediction, and tailored products (Indicator 2.1.1). Additional coordination is needed between public health agencies and other agencies to prepare for and respond to climate impacts. This should include efforts to strengthen public health capacity for assessing vulnerability; surveillance and early warning systems; climate adaptation planning; disaster response; and research, monitoring, and evaluation to inform climate responses at the local level. Investments should target vulnerable populations. For instance, the CDC has recognized the unique vulnerabilities of rural communities and developed plans for rural public health preparedness and response capacity.c94 Similar investments are needed to protect other vulnerable groups.

Public health systems can play a central role in integrating health into policies in other sectors including housing, urban and rural planning and development, energy, food, and education. Investments in public health programs should support such cross-sector leadership. Public health education and communication on the harms of fossil fuels and climate change are also important for increasing community preparedness and resilience. There is also an opportunity to draw on lessons from public health communications campaigns on other industries and commercial determinants of health, such as tobacco, to address rising misinformation.

Recommendation 2.3. Leverage infrastructure and built environment investments to maximize community health and resilience

Homes, schools, libraries, healthcare systems, and other social and built infrastructure can be sources of community resilience by protecting people from climate risks such as heat, flooding, wildfire, and air pollution. This approach also strengthens the social connectedness needed to prepare for and cope with climate impacts. However, such infrastructure and needs are also highly vulnerable to climate impacts, particularly in frontline communities that face disproportionate environmental hazards and health risks. Decades of disinvestment, structural racism, and discriminatory policies have contributed to higher exposures to air pollution and climate risks, as well as reduced access to adaptation strategies such as urban greening, in these communities.c95, c96, c97, c98

The IRA includes funding for community and household climate resilience. For instance, the Environmental and Climate Justice Block Grants program supports adaptation efforts in disadvantaged communities, including community efforts to monitor, prevent, and remediate air pollution, reduce indoor toxins, and address and assess effectiveness of reducing climate-related health risks. IRA financing for weatherization, energy efficiency, air pollution reduction, and adaptation can also support healthy and affordable housing for the elderly, people with disabilities, and Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Section 8 program participants.c99, c100, c101 Other federal agencies, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), also have funding programs for community climate resilience.

These and other programs can potentially improve health while meeting climate goals. For example, electrification of home heating and cooling, such as through subsidies for heat pumps, can improve indoor air pollution and deliver energy cost savings for families, while also reducing GHG emissions. Investments in decentralized renewable grids and geothermal district heating and cooling can also increase health and resilience. Investments in reflective and porous city surfaces can reduce heat absorption and flooding.

For these and similar investments to best protect health, they must be targeted to the most impacted communities. In 2021, low-income households received just 13% of electric and gas utility energy efficiency spending despite making up 27.5% of U.S. households.c102 Further prioritization of investments in environmental justice, such as the Justice 40 initiatives, is essential to promote optimal community health and resilience.

Support and expand community resilience hubs

Resilience hubs are community-based spaces (e.g., libraries, churches, community centers, and schools) that are embedded in and trusted by the community. They can serve as anchors for community preparedness, connection, and integrated health and social services before, during, and after climate and health emergencies.c103

Resilience hubs offer one model for investment in community preparedness and adaptation to protect people from climate change’s physical and mental health impacts.104 Resilience hubs can provide a diversity of services to communities including information and communications, economic and social support, planning support, and linkages to health and other social services, among other support functions.c104 These hubs can play a vital role in the ability of the community to address social determinants of health and enhance health equity by linking community members with essential services.c103 Expanded support for community resilience hubs, including through the IRA’s community resilience programs and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Hazard Mitigation program, offers a promising pathway to greater climate and health equity.

Build U.S. global leadership through scaling up global investments and support for climate and health action.

Build U.S. global leadership through scaling up global investments and support for climate and health action.

Increasing the amount and accessibility of climate finance is essential to unlock the scale of climate action needed to achieve global climate goals.c105 In recent years, the U.S. has made meaningful commitments to invest in climate action. Still, more ambitious, sustainable, accessible, and predictable investments are required to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement and drive health equity in the U.S. and globally.c105, c106 This includes opportunities for global leadership at the 29th Conference of the Parties in Azerbaijan (COP29) and ambitious domestic policies when the U.S. updates its national emissions reduction target in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC).

Recommendation 3.1: Expand U.S. contributions to global climate finance in line with need and the scale of investments in other global challenges

The U.S. is the most significant contributor to cumulative GHG emissions and continues to be one of the largest contributors to global GHG emissions,c107 while the health and economic impacts of climate change fall most heavily on low-emitting countries.c108, c109, c110 The U.S. committed to increasing international public climate finance to over $11 billion USD by 2024, including through pledges to provide $3 billion USD to the Green Climate Fund’s second replenishment and expand adaptation finance to $3 billion USD annually through the President’s Emergency Plan for Action and Resilience (PREPARE), as well as support finance mobilization efforts such as the Global Methane Pledge and Methane Finance Sprint.c111, c112, c113 The U.S. contributed $5.8 billion USD in international public climate finance in 2022, an estimated $9.5 billion USD in 2023, and is on track to meet the $11 billion USD goal in 2024.c114 Yet, climate investments fall far short of the financing needed to safeguard health from deepening climate impacts.c115, c116

Support ambitious collective commitments for global climate finance

In 2009, high-income countries committed to mobilizing $100 billion USD annually in climate finance to support low- and middle-income countries in meeting decarbonization and adaptation goals. At COP29, countries will negotiate a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) – updating the $100 billion USD commitment and laying the foundation for scaled-up climate finance.c117 The U.S. should support an ambitious, needs-based NCQG that prioritizes high-quality and accessible finance across mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage. Financial investments should meet the needs of impacted countries to achieve emission reduction goals through mitigation efforts that enhance access to clean and healthy energy, support economic development, and improve local air quality. The NCQG should include significantly scaled up finance for adaptation and resilience measures to prepare for and respond to accelerating climate impacts, including investments in healthy and resilient communities and health systems. The U.S. should additionally support finance for loss and damage through the NCQG and direct investment in the Loss and Damage fund.

Recommendation 3.2: Retool global climate, health, and development investments to achieve interconnected climate and health goals

The U.S. is a large contributor to global health initiatives through its development assistance programs and its contributions to multilateral institutions.c118 Development agencies, including the U.S. Agency for International Development and the State Department should prioritize increasing climate and health investments across sectors. Specific examples include integrating climate across health programs; building climate-resilient communities; ensuring sustainable, resilient, healthy, and nutritionally viable food systems; and expanding equitable access to clean and affordable energy. Such efforts should include developing public health systems that protect community health and manage the health response to climate emergencies.

Likewise, development agencies across the U.S. government should elevate health considerations and health outcomes as priorities across climate investments in all sectors, supporting climate action that improves air quality and other environmental determinants of health equity. Investments should explicitly target the countries and communities most impacted by the health harms of climate change and that have contributed the least to climate pollution, and should provide direct support for country- and community-led initiatives that center the priorities and needs of the most impacted.c119

Recommendation 3.3: Support changes to the global financial architecture, including debt structures, to enable greater investment in health and social systems

More investment alone will not be enough. Financing must be equitable, not place a greater economic burden on low- and middle-income people and communities, and should not support activities that harm health or the climate. Internationally, the U.S. should scale up grant-based climate finance without deepening the debt crisis that erodes the ability of low- and middle-income countries to invest in their national climate, health, and development efforts.

National climate investments should support a just transition that improves health by prioritizing high-quality jobs, driving economic investment and support for workers and communities most affected by the transition to renewable energy. It is critical to ensure that low- and middle-income communities have equitable access to healthy, affordable, reliable energy and resilience and adaptation solutions.

Investing in prevention – through strong public health programs, resilient and equitable communities, and climate action to forestall worsening health impacts – makes economic sense. Delaying investment now will require more investment later to manage accelerating climate impacts on human health and well-being, our societies, and our economies.

Invest in climate and health research

Health impact assessments of clean energy infrastructure and other mitigation technologies is required to inform health-centered mitigation and adaptation planning and implementation. Current research initiatives are underfunded and focus on understanding climate and health impacts.c120 In 2023, for instance, 83% of all papers published globally on climate change and health focused on impacts; for papers that focused on the U.S., 64% were about impacts, while 5% focused on adaptation and 7% focused on mitigation (Indicator 5.3.1).

There are promising new investments underway to accelerate climate and health research, including the National Integrated Heat-Health Information System centers of excellence focused on heat and health, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)’s Grand Challenge on Climate Change, Human Health, and Equity, alongside efforts by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), EPA, HHS, NASA, and others to broaden funding for health, environmental justice, and climate change research.

The U.S. should substantially scale up investments in forward-looking health and climate action research, such as through the NIH Climate Change and Health Initiative, the CDC Climate and Health Program, and other national research institutes.c121 Investments in research must be accompanied by scaled-up efforts to translate research into policy and investment in action to implement evidence-based climate and health policies and programs at all levels.

Conclusion

New Findings: Key U.S.-specific Indicators from the 2024 Lancet Countdown Report

HEAT AND HEALTH

Exposure to high temperatures threatens people’s lives, health, and wellbeing, leading to death and heat-related disease, and increasing healthcare demand during heatwave episodes. Older people, socio-economically deprived communities, very young children, pregnant people, and those with underlying health problems are particularly at risk.

- Indicator 1.1.1:

From 2014-2023, each infant and adult over age 65 was exposed to 9.3 and 8.4 heatwave days per year, respectively. This was more than double what it was from 1986-2005. - Indicator 1.1.2:

From 2014-2023, individuals were exposed to a moderate or higher risk of heat stress for nearly 600 hours per year during light outdoor activity (like walking).

Green space promotes numerous health benefits and reduces heat exposure.

- Indicator 2.2.3:

In 2023, out of 49 U.S. urban centers evaluated, 21 (43%) had moderate levels of green space, and 4 (8%) had high levels. Meanwhile, 15 (31%) had low, 5 (10%) had very low, and 4 (8%) had exceptionally low levels of greenness. This is a decline from 2020 when 28 (57%) urban centers had moderate levels of greenness or above.

Heat exposure limits labor productivity, which undermines livelihoods and the social determinants of health.

- Indicator 1.1.3:

3.4 billion potential labor hours were lost due to heat exposure in 2023, an increase of 69% from the 1990-1999 annual average. - Indicator 4.1.3:

US$103 billion was the potential loss of income from reduced labor due to heat in 2023 – this is a record high.

VULNERABILITY TO INFECTIOUS DISEASES

The suitability for transmission of many infectious diseases, including vector-borne, food-borne, and water-borne diseases, is influenced by shifts in temperature and precipitation associated with climate change.

- Indicator 1.3.2:

From 2014-2023 there were an average of 1.7 months and 2.3 months per year when conditions in U.S. lowlands (<1500m) were suitable for the spread of malaria by P. falciparum and P. vivax, respectively. This was an increase of 39.7% and 32.1%, respectively, compared to the 1951-1960 average. - Indicator 1.3.3:

From 2014-2023, the length of coastline with conditions suitable for the transmission of Vibrio pathogens at any given time during the year was 50% greater than in 2000-2004. In these last 10 years, the average annual population living within 100 km from coastal waters with conditions suitable for Vibrio transmission reached 66 million.

AIR POLLUTION, ENERGY TRANSITION AND HEALTH CO-BENEFITS

The low adoption of clean renewable energy and the continued use of fossil fuels and biomass lead to high levels of air pollution, which increases the risk of respiratory and cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, diabetes, neurological disorders, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and leads to a high burden of disease and mortality. All of these lead to increasing demand on care services.

- Indicator 3.1.1:

In 2022, renewable energy accounted for only 3.1% of the total energy supply in the U.S., and coal made up 11%. - Indicator 3.1.1:

Although annual CO₂ emissions from the U.S. energy system have been slowly decreasing since 2000, they increased 7% from 2020 to 2021 – the largest year on year increase in two decades. - Indicator 3.1.3:

In 2021, fossil fuels accounted for more than 93% of all road transport energy, and electricity accounted for less than 1%. - Indicator 3.2.1:

In 2021, there were approximately 125,800 deaths attributable to anthropogenic air pollution (PM2.5) in the U.S.. Fossil fuels contributed to 39% of these deaths (about 50,000 deaths).* - Indicator 4.1.4:

U.S. $669 billion is the monetised value of premature mortality due to anthropogenic air pollution in 2021. - Indicator 4.2.5:

In 2022, the U.S. contributed 15.9% of the world’s consumption-based CO2 emissions. For a production-based accounting, the U.S. contributed 13.5% of the world’s CO2 emissions. The U.S. was the world’s second-highest emitter of CO2 based on both consumption- and production-based accounting. By either accounting, the U.S. is the world’s second greatest emitter of CO2. - Indicator 4.3.3:

In 2022, the U.S. had a net-negative carbon revenue, indicating that fossil fuel subsidies were higher than carbon prices. The country allocated a net total of over U.S.$9 billion in fossil fuel subsidies in 2022 alone.

*In this estimate, fossil fuels include coal and liquid gas.

ENGAGEMENT IN HEALTH AND CLIMATE CHANGE

To respond to the health impacts of climate change, locally relevant data and research is required to inform policies and to enable governments to take a leading role in championing health-centered climate action on mitigation and adaptation within the U.S. in international negotiations.

- Indicator 2.1.3:

Over 80% of U.S. cities reporting on their climate action have undertaken a climate risk and vulnerability assessment. - Indicator 5.3.1:

In 2023, for instance, 83% of all papers published globally on climate change and health focused on impacts; for papers that focused on the U.S., 64% were about impacts, while 5% focused on adaptation and 7% focused on mitigation.

Organizations

THE LANCET COUNTDOWN

The Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change is a multi-disciplinary collaboration monitoring the links between health and climate change. In 2024, we published the 8th Lancet Countdown annual indicator report, funded by Wellcome and developed in close collaboration with the World Health Organization. The report represents the work of 122 leading experts from 57 academic institutions and UN agencies globally. Published ahead of the 29th UN Conference of the Parties (COP), the report provides the most up-to-date assessment of the links between health and climate change. For its 2024 assessment, visit https://www.lancetcountdown.org/.

THE AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION

The American Public Health Association (APHA) champions the health of all people and all communities. It strengthens the public health profession, promotes best practices, and shares the latest public health research and information. The APHA is the only organization that influences federal policy, has a nearly 150-year perspective, and brings together members from all fields of public health. In 2019, APHA also launched the Center for Climate, Health and Equity. APHA’s Center for Climate, Health and Equity is at the forefront of public health efforts to advance policy, shape the narrative, and galvanize the public health field to address climate change. Best positioned to power, resource and connect a movement of public health professionals and their partners in the pursuit of climate justice and equitable health outcomes, the Center works to raise awareness of the public health implications of climate change; promote community centered policies anchored in climate equity; and convene, train, mobilize and amplify trusted public health voices to influence policy and engage with their communities.

Acknowledgements

U.S. Policy Brief Authors: Naomi S. Beyeler, PhD, MPH, MCP; Jonathan Buonocore, ScD; Julia Gohlke, PhD; Shaneeta Johnson, MD, MBA; Renee N. Salas, MD, MPH, MS; Jeremy J. Hess, MD, MPH.

Additional Team Acknowledgements: Support, logistics and review: Marci Burden, MA; Spanish translation review and copy editing: Juan Aguilera, MD, PhD, MPH; Website design: Huck Strategies. Thank you to the Climate and Health Foundation for their generous support.

Review on Behalf of the Lancet Countdown (alphabetical): Camile Oliveira, MPhil; Marina Romanello, PhD; Maria Walawender, MSPH.

Review on Behalf of the American Public Health Association (alphabetical): Katherine Catalano, MS.

Science and Technical Advisors (alphabetical): These science and technical advisors provided technical review and assistance but are not responsible for the content of the report, and this report does not represent the views of their respective federal institutions. Caitlin A. Gould, DrPH, MPPA; Rhonda J. Moore, PhD.

U.S. Brief Working Group Reviewers of Brief (alphabetical): Juan Aguilera, MD, PhD, MPH; A. Karim Ahmed, PhD; Mona Arora, PhD, MSPH; Elizabeth Bechard, MScPH; Laura Bozzi, PhD; Robert Byron, MD, MPH; Amy Collins, MD; Cara Cook, MS, RN, AHN-BC; Michael A. Diefenbach, PhD; Caleb Dresser, MD, MPH; Kristie L. Ebi, PhD, MPH; Yun Hang, PhD, MS; Heidi Honegger Rogers, DNP, FNP-C, APHN-BN, FNAP; Ans Irfan, MD, EdD, DrPH, ScD, MPH, MRPL; Rachel Lookadoo, JD; Edward Maibach, MPH, PhD; Leyla McCurdy, MPhil; Jennifer Monroe Zakaras, MPH; Lisa Patel, MD, MESc, FAAP; Jonathan Patz, MD, MPH; Alixandra Rachman, MPH; Angana Roy, MPH; Linda Rudolph, MD, MPH; Liz Scott; Emily Senay, MD, MPH; Jodi D. Sherman, MD; Vishnu Laalitha Surapaneni, MD, MPH; Nova Marie Tebbe, MPH, MPA; J. Jason West, MS, MPhil, PhD; Kristi E. White, PhD, ABPP; Carol C. Ziegler, DNP, APRN, FNP-C; Lewis H. Ziska, PhD.

Recommended Citation

Lancet Countdown, 2024: 2024 Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change Policy Brief for the United States of America. Beyeler NS, Buonocore J, Gohlke J, Johnson S, Salas RN, Hess JJ. Lancet Countdown U.S. Policy Brief, London, United Kingdom, 20 pp.

Introduction Recommendations 1. Reduce Fossil Fuel Production 2. Build Resilience 3. Build Global Leadership Conclusion Key Indicators – Heat and Health – Vulnerability to Infectious Disease – Air Pollution, Energy Transition and Health Co-Benefits – Engagement in Health and Climate Change Organizations Acknowledgements